‘On the throne of the world, any delusion can become fact’.

Gore Vidal, Julian (1964).

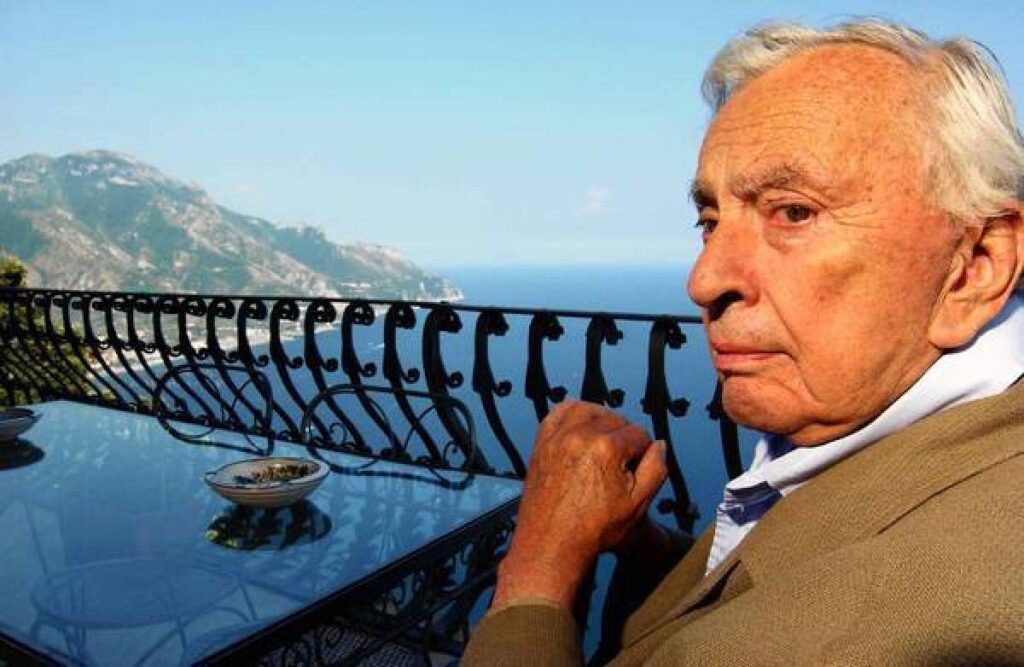

When Gore Vidal died in July 2012, Barack Obama was president of the United States, the United Kingdom was still part of the European Union, and Donald Trump was simply the brash, billionaire-businessman star of The Apprentice. The cultural fallout from the #metoo and Black Lives Matter movements had not occurred, and the Covid-19 pandemic and the wars in Ukraine and Gaza were still a decade away. Most notably, Vidal never lived to see the two-time Trump administration, which has arguably altered the complexion of his nation more than any other event since his death. But Vidal had seen enough of the world during his nearly nine decades in it for none of these events likely to be a surprise to him. As he famously remarked, the four sweetest words in the English language were ‘I told you so’.

On 3 October 2025, Gore Vidal would have been 100, making this a useful juncture to reconsider his legacy. A quick search of Google Trends reveals occasional interest in Vidal since his death, often around American presidential elections. The success of the Broadway musical Hamilton (2015- ) occasioned renewed interest in Vidal’s novel Burr (1973), which had traversed much of the same historical ground. Meanwhile, the republication of his satirical novel Myra Breckinridge (1968) in 2019 (featuring a new introduction by the feminist literary critic Camille Paglia) sought to chime with recent debates about gender ideology and trans- rights. Elsewhere, the play Best of Enemies (2021) by James Graham dramatised Vidal’s 1968 debates with William F. Buckley and received critical praise for capturing their dynamic on the London West-End stage. This autumn, the Houghton Library at Harvard University is presenting ‘Gore Vidal Goes to the Movies’, screening of some of Vidal’s film projects, including Ben-Hur (1958) and Caligula (1979). But there has been little recent investment in Gore Vidal’s legacy by his publisher, Penguin Random House, apart from the republication of Julian this year, with a new introduction by his biographer Jay Parini.

Indeed, in comparison to his literary contemporaries, Gore Vidal has been rather ill served by posterity since his death. John Updike, Norman Mailer, Saul Bellow and Cormac McCarthy have all had societies formed dedicated to the study of their thought and writings. Born six weeks after Vidal, William F. Buckley’s centennial has already been marked by the publication of an authorised biography by Sam Tanenhaus and another by Lawrence Perelman. None of Vidal’s works have yet been published as part of the Library of America, which was designed as a project to preserve the American literary canon. Nor are you likely to find any of Gore Vidal’s novels on any academic curricula on twentieth-century American literature. But, throughout his career, Vidal had often complained about his exclusion from the American literary establishment. For instance, he narrowly missed out on being awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his novel Lincoln (1984); the three judges having recommended him for the prize, but being overruled by the general Pulitzer committee.

Gore Vidal always liked to project himself as a seer who could see into the future. He inherited this tendency from his grandfather, Thomas Pryor Gore, the blind Democratic senator from Oklahoma, who had often predicted disaster for the United States. Alongside the American history novels that made his name, many of Gore Vidal’s novels imagined apocalyptic scenarios, such as those of Messiah (1954) and Kalki (1978). In the former work, a cult religion called Cavism sweeps the globe and destroys Christian civilisation, while the latter depicts the actual annihilation of humanity by another religious guru, this time inspired by Eastern mysticism. Suffice to say, although positioning himself as a prophet, Gore Vidal did not have a rosy view of the future.

If Gore Vidal’s ghost were to venture abroad in his home country today, he would encounter a nation whose transformation might have horrified him. Yet he might also feel a sense of schadenfreude that his prescience had been so accurate in many respects about the shape of the political changes that have overtaken the United States over the past decade. As American culture grapples with the fallout of increasing polarisation, institutional mistrust and global repositioning, many of Vidal’s essays and speeches seem to resonate with prophecy about the likelihood of these developments. While undoubtedly deploring the political rise of Donald Trump and the MAGA movement, Vidal would have seen in them a rejection of the establishment politics of ‘business as usual’ that he, too, had long ranged himself against.

Indeed, Vidal would have been in favour of some of the Trump administration’s isolationist and protectionist policies, which accord with his own views about American international withdrawal and economic independence. But the Pentagon’s ballooning military budget and the continued chauvinism of American foreign policy would have confirmed his worst fears about the direction of the United States. More than anything, however, it is likely that the coarsening of political dialogue since 2012 that would have disgusted Vidal the most. For a man who valued intellect, wit and reason above all else, the bald-faced demagoguery of the Trump era would have appalled him. In the era of ‘fake news’, the style and substance of Vidal’s 1960s debates with William F. Buckley are far removed from the mudslinging shouting matches that have come to characterise sadly even American presidential debates.

Although elitist in the way he projected himself, Gore Vidal strongly criticised America’s economic inequality throughout his career. He foresaw a widening gap between America’s haves and have-nots. Since 2012, this gulf has only grown wider. In 2025, the top 1% of Americans owns 32% of the nation’s wealth and real wages have stagnated despite low unemployment levels. While the rise of movements such as Occupy Wall Street and Bernie Sanders’ progressive lobby have echoed Vidal’s call for systematic reform, their limited success seems to confirm his cynicism about revolutionary change ever being possible within any corporate-dominated political framework. For most of his career, Vidal’s offensive against corporate America was aimed at the oil industry, but his final years saw Big Oil give way to the domination of Big Tech.

When Vidal died in 2012, Amazon, Facebook and Twitter were already major companies, but they have only tightened their grip on the world since, alongside new companies like TikTok. In addition, many tech billionaires have entered the social, cultural and political fray to advance their own agendas beyond the limits of their own corporate organisations. The global influence of this oligarchy on the development of social media and data-collection systems would have appalled Vidal, who understood the important roles played by knowledge, privacy and independence in society. Moreover, Vidal’s warnings about media consolidation (at that time, regarding television and print media) seem quaint in an age where algorithms do more to shape public opinion than broadcasters or journalists. As someone who never advanced beyond pen, paper and typewriter, artificial intelligence would have horrified Vidal. He would view it with great suspicion, fearful of its potential to amplify propaganda and dilute critical thought, let alone the negative effect it would have on the creative industries.

Finally, Gore Vidal would be unsurprised at the culture wars that have defined the past decade and a half, metastasising and intensifying as a result of social media. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, he traced their origins in a series of essays, and usually supported the greater liberalisation of society, especially regarding sexuality. But he also came to view these polarising culture wars as ways for the global elites to obscure the continued economic exploitation that affected left and right alike. Vidal had been outspoken throughout his career about the powerful roles played in human society by sexuality and gender. As the author of the satirical novels, Myra Breckinridge (1968) and Myron (1974), which depict a transgender protagonist, he would understand the cultural significance gender ideology has assumed today. Extolling the virtues of free speech to the grave, Vidal would likely still have inveighed against left and right alike; attacking the left for its moralising censorship and the right for its selective outrage over ‘wokeness’. Yet, considering his appetite for controversy, the outspoken Vidal would probably have found himself ‘cancelled’ at some point, too.

Which of Vidal’s works will stand the test of time? Above all, one could argue that Julian (1964) was arguably Vidal’s greatest novel and one that will last as long as there are readers left to read it. Yet, some of his other novels have claims to posterity. The City and the Pillar (1948) was a landmark in gay fiction and a brave work to write in any era. His play The Best Man (1960) was such a neat depiction of American political rivalry that it gets revived every presidential election cycle. Some of his essays, too, such as ‘The Second American Revolution’, ‘Monotheism and its Discontents’ and ‘Sex is Politics’, retain their eloquence, force and relevance. If Vidal himself was asked for his greatest literary accomplishment, he might have nominated his Narratives of Empire (1967-2000) cycle of novels, especially Lincoln (1984). Lastly, his memoir Palimpsest (1995) has some claim to be one of the most fascinating literary autobiographies of the later twentieth century, depicting Vidal’s Zelig-like ability to turn up at the most opportune moments in American history.

Gore Vidal’s mortal remains were laid to rest in Section E, Lot 293½ of Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington D.C. But one must wonder if his spirit can rest when his country remains in such a state of turmoil. I suspect that his ghost is still abroad, haunting the corridors of power and the galleries of culture. Yet, perhaps, his outspoken egotism and self-promotion during his lifetime have somewhat obstructed his rendezvous with posterity. Although now himself another ‘dead white male’, Vidal was often clairvoyant about the trajectory of culture and society in his own country and beyond. In his final decades, Vidal often referred to his homeland as ‘the United States of Amnesia’ because of its tendency to forget its own culture and history. But, as it negotiates one of the most turbulent and uncertain eras of its existence, America would be well to remember Vidal’s voice and opinions in order to ensure that it does not forget entirely who it is and where it has come from. Gore Vidal remains worth reading, and worth heeding.